From beads on sticks to boxes that silently judge our passwords

Humanity has always had two great fears:

- That we’ll run out of tea.

- That someone, somewhere, will ask us to do long division.

To avoid the latter, civilisations have spent thousands of years inventing gadgets to do the thinking for us. Here is their story, or at least the version any half-awake historian would produce after an extended pub lunch.

The Abacus:

The original pocket calculator, but without pockets.

Invented so long ago that even the people who invented it cannot remember doing so, the abacus quickly became the must-have item for merchants, traders, and anyone whose job involved counting beyond ten fingers.

It was portable (ish), intuitive (if you were patient), and never needed batteries, unless you threw it at someone and broke it.

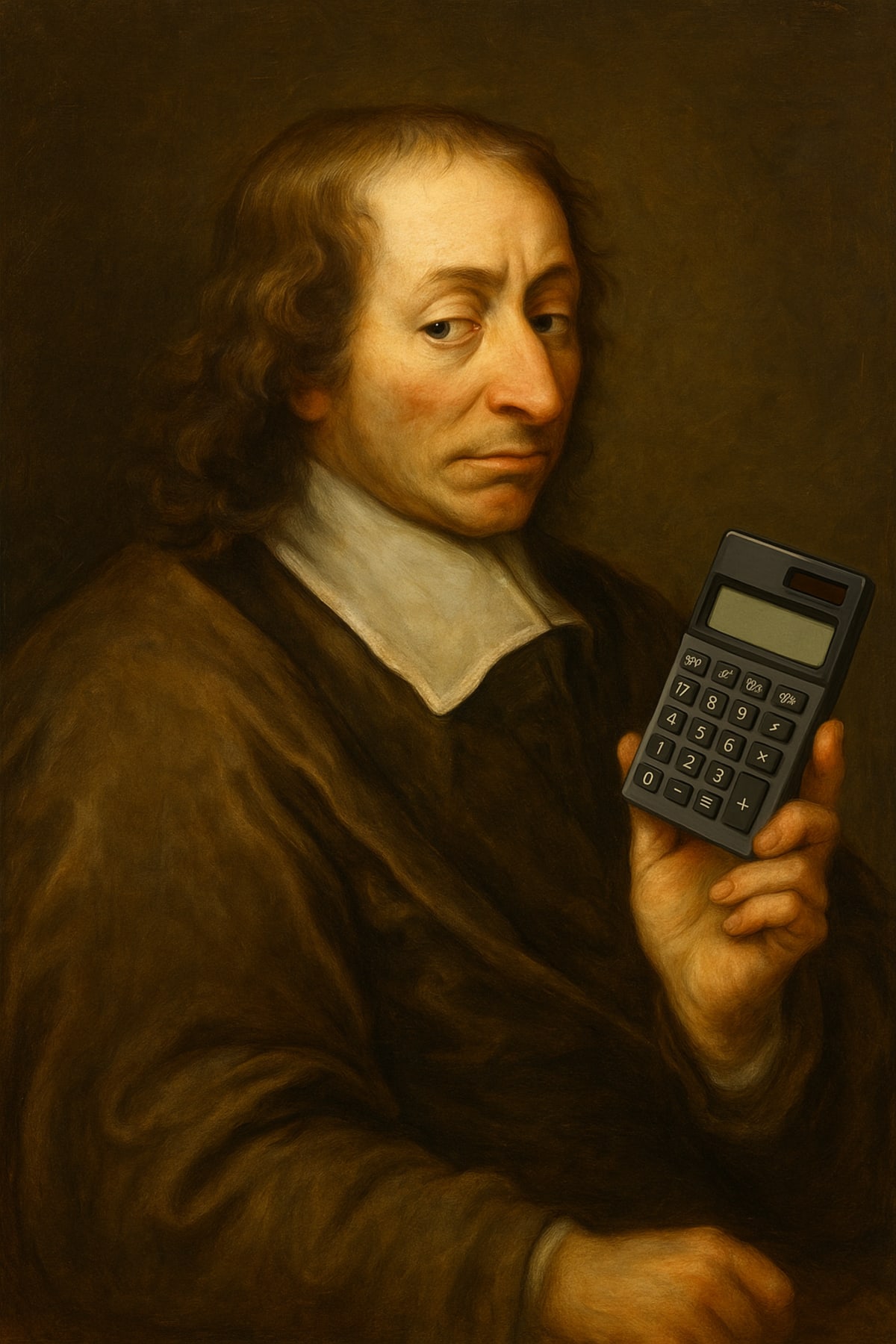

Blaise Pascal’s La Pascaline:

Because even in the 1640s the French were allergic to arithmetic.

Enter Blaise Pascal, (see main image) a mathematician, philosopher, inventor and presumably someone who despised doing sums for his tax collector father.

In 1642 he created the Pascaline, a machine of gears, wheels, and elegant woodwork designed to add and subtract without tears.

It was a marvel of its time.

It could perform calculations faster than a monk with a quill.

It was so advanced that a Paris court in 2025 still panicked at the idea of it leaving the country.

Not bad for a 382-year-old adding machine.

Charles Babbage’s Engines:

The Victorian “what if” machine.

In the 1800s, Charles Babbage took one look at the Pascaline and said, “Lovely bit of kit, but what if we make it bigger?”

Bigger it became, so big, in fact, that Victorian engineers quietly wept into their cravats.

The Analytical Engine promised programmable calculations, punch cards, and enough brass to bankrupt Birmingham.

Ada Lovelace wrote the first algorithm for a computer that didn’t yet exist. Cheeky, visionary, and absolutely on brand for the 19th century.

Slide Rules:

The thinking person’s ruler that nobody asked for.

Fast forward a century or so, and the slide rule arrived: a device engineers wielded with such confidence that nobody dared admit they didn’t know how it worked.

You slid bits of wood.

Numbers appeared.

Planes flew.

Nobody questioned it.

The Electronic Calculator:

The swinging Sixties, but for mathematics.

By the 1970s, calculators were all the rage, chunky, beige, and powered by more AA batteries than the Apollo programme.

Teachers claimed they would “rot your brain.”

Children loved them anyway.

Adults used them to calculate mortgages and then promptly wished they hadn’t.

The Pocket Calculator:

When your maths homework suddenly became doable.

Then came small, cheap, ubiquitous calculators.

Every child had one.

Every exam board banned them.

Every adult kept one in a kitchen drawer filled with miscellaneous screws.

The Computer Age:

Babbage’s ghost cheers quietly.

Laptops, desktops, tablets, suddenly arithmetic could be done by machines that also played solitaire, wrote emails, and flashed passive-aggressive low battery warnings.

Smartphones:

The final boss of numerical laziness.

Behold: a device capable of storing the entirety of human knowledge.

Most people used it to calculate restaurant tips.

The 21st Century and Beyond:

Devices no one asked for, but we’ll buy anyway.

Designers are now working on:

- AI calculators that correct your mathematical errors and your life choices.

- Smart spectacles that solve equations before you’ve even understood the question.

- Implantable computing chips that whisper the answer directly into your brain (side effects include knowing pi to 4,000 places and an irresistible urge to join Mensa).

- Quantum calculators which simultaneously give you the right answer, the wrong answer, and a polite message saying it cannot confirm either.

At this rate, by 2050 all maths will be performed by appliances we’ve forgotten the Wi-Fi passwords for.

In conclusion:

From wooden beads to quantum boxes, humanity has spent millennia trying not to add up things manually. Blaise Pascal would be proud, and possibly bemused, to know that his wooden wonder is now treated like a national treasure.

Meanwhile, the rest of us remain grateful that machines continue to save us from arithmetic-induced headaches.

Copyright © Tom Kane November 2025

Writing a fiction novel is also a calculated risk. You never know if anyone is going to buy a copy. So, take a peek at my novels and see if anything catches your eye. Some of them are calculated to to make you smile. Click here.