Time travel is one of those ideas that refuses to behave. The moment it appears in fiction, it starts asking awkward questions. Can you change the past. Should you. And if you do, who pays the price.

For well over a century, writers and filmmakers have used time travel not simply as a spectacle, but as a lens through which to examine regret, destiny, and consequence.

Time Travel on Television

Television thrives on the elasticity of time travel. Doctor Who treats time as a playground, yet constantly returns to the cost of interference. Every fixed point carries a moral weight.

At the other end of the tonal spectrum, Dark presents time as a closed loop, where choice is an illusion and causality is merciless. Shows like Quantum Leap and 12 Monkeys sit somewhere in between, balancing hope with inevitability.

Television excels at showing us the emotional whiplash of time travel. Lives half-remembered. Futures glimpsed and lost.

Time Travel in Film

Cinema often makes time travel visceral. Back to the Future gave us paradoxes wrapped in charm, while Interstellar leaned into real physics, exploring time dilation and gravitational extremes.

More unsettling are films like Looper and Primer, where the mechanics are deliberately opaque. These stories suggest that once time becomes a tool, it also becomes a trap.

The Stranger Theories

Beyond fiction lie theories that range from plausible to deeply unsettling. Wormholes, if they exist, might allow shortcuts through spacetime. Closed timelike curves suggest that time could loop back on itself, neatly sidestepping paradoxes by ensuring everything that happens has already happened.

Then there are the more outlandish ideas. Parallel timelines spawning with every decision. The universe as a self-correcting organism, erasing anomalies. Or the notion that time itself is not fundamental at all, but an emergent illusion created by consciousness.

Science has not proven time travel is possible. But it also has not entirely ruled it out.

Time Travel in Books

The modern conversation arguably begins with The Time Machine, where H. G. Wells used time travel to critique class division and human stagnation rather than to stage paradoxes. From there, literature took the idea in increasingly personal directions.

Stephen King’s 11/22/63 asks whether preventing tragedy is worth the collateral damage, while Octavia Butler’s Kindred uses involuntary time travel to confront the brutal realities of history. Connie Willis, in Doomsday Book, blends academic curiosity with emotional devastation, reminding us that the past is not an abstraction. It bleeds.

In fiction, time travel is rarely about gadgets. It is about responsibility.

Why We Keep Returning to Time

Perhaps the real reason time travel endures is simple. It externalises the most human impulse of all. The desire to go back, to fix one moment, one mistake, one loss.

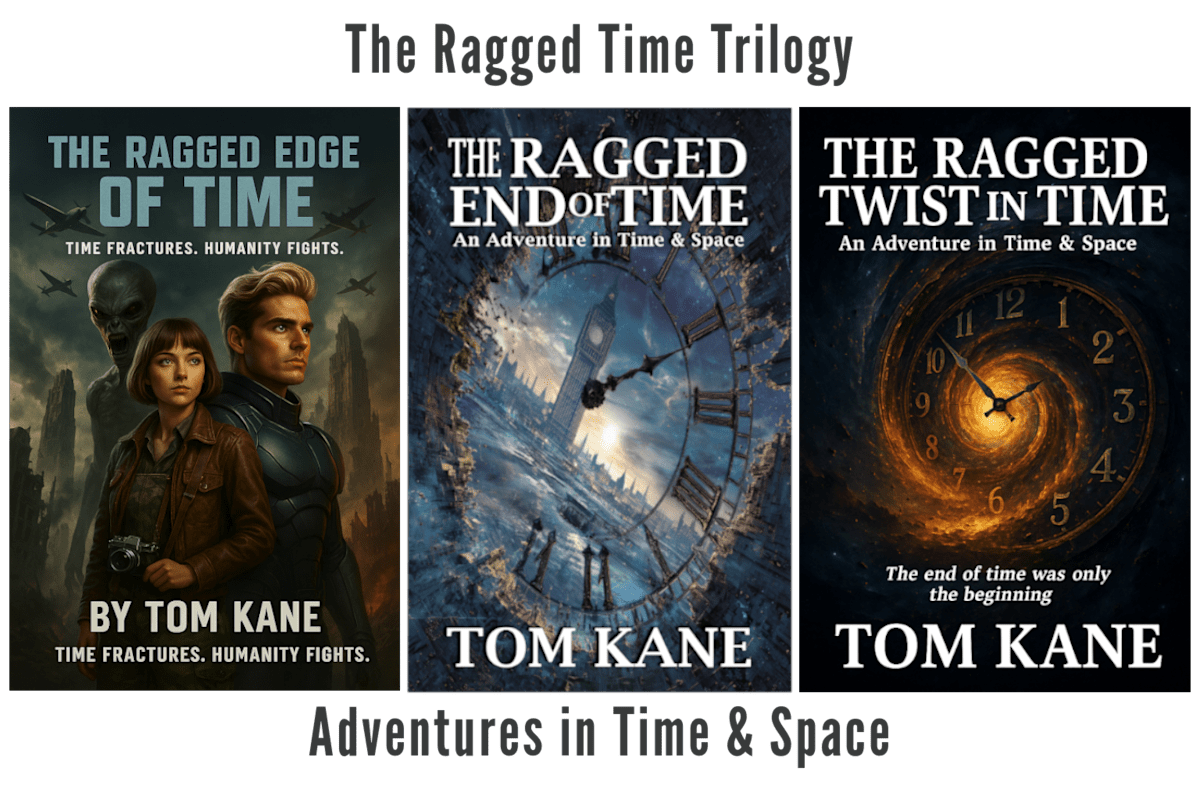

That question sits at the heart of my own work on The Ragged Time Trilogy. Rather than treating time as a neat corridor, the trilogy explores it as something frayed and dangerous. A force that resists being used, and exacts a price when it is.

Time travel, in the end, is not about machines or equations. It is about consequences. And the uncomfortable truth that some things, no matter how much we wish otherwise, may be better left untouched.

Copyright © Tom Kane 2026